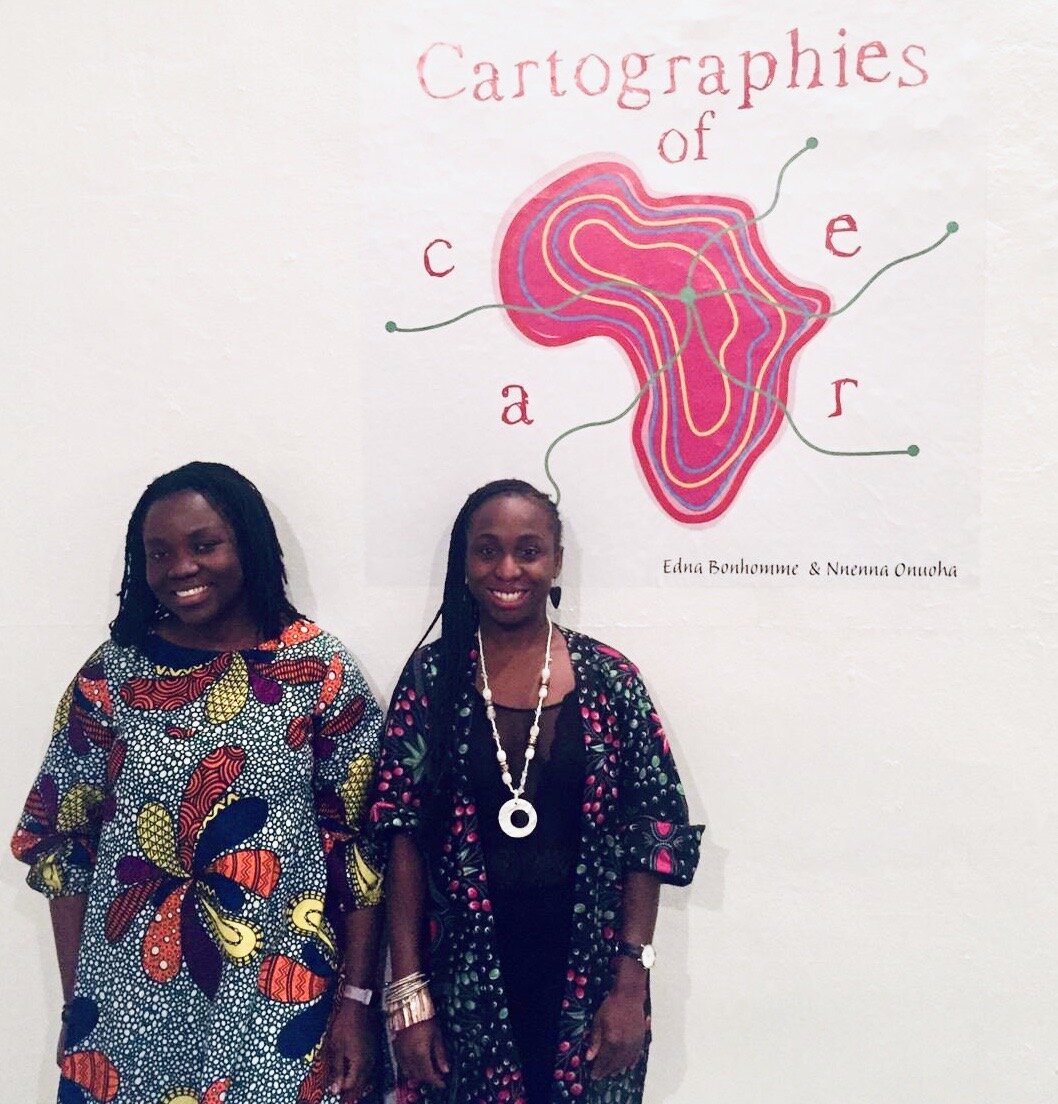

My latest article in Griot Mag.

2 in 1 Salon, Joe Slovo Park, Cape Town, South Africa – via Wikimedia commons

“Where are you from?” I am often arrested or annoyed by this question. However, I was in Durban, South Africa and since this query was posed by a Black woman, I politely answered. “I’m from the United States and I live in Germany.” I stood at the entrance of a nearly empty Black hair salon, where the woodwind percussion of the South African artist Sjava blasted through the speakers. Before me were 5 Black women and one customer. I was wearing a black jacket, a black turtleneck, and high-waisted bleached stained jeans. I gazed sternly at the women, with the expectation that I would enter this portal for my beauty regime and manage the dwarfish Afro that lay close to my scalp. They looked dubious and increasingly became curious about my accent, my outfit, and my septum piercing. So as they suspected, I must be a stranger.At first, no one wanted to braid my hair. One person remarked, It’s too short. Another concurred, it will be difficult to grab your hair for the braid. To my chagrin, I made the case that I wanted a fresh look for the New Year, as a traveler from across the street, I wanted to support Black women in their craft. After some negotiation between the staff in English, Sara began to braid my hair. The other four continued texting on their phones, chatting and dancing to Afrobeats.

The contours of segregation in South Africa look different today, and on my journey, I began to unravel its complicated and coded layers.

The tragedy of the South African post-apartheid state is that space, land, and resources are highly divided along racial and gendered lines. In Durban, it was shocking to see how segregated public spaces were. On a sunny day, while walking along the beach, my partner and I found ourselves only among Black, South Asian descended and other people of color. At the pier, we watched the container ships go by, lovers taking selfies, and young children riding their bicycles. Other than my partner, no white people were occupying this public space. We wondered, where all the white people were until we passed by a yacht club, with its “members only” sign, and bore witness to this seaside white flight 100 meters from the pier. The contours of segregation in South Africa look different today, and on my journey, I began to unravel its complicated and coded layers.

Sign in Durban that states the beach is for whites only under section 37 of the Durban beach by-laws. The languages are English, Afrikaans and Zulu, the language of the black population group in the Durban area (1989), via wikimedia commons

Nevertheless, Black women gather in their own intimate spaces—in kitchens and salons. From Inua Ellams’s Barbershop chronicles to the gaudy rendition of Black salons by Tyler Perry, Black grooming spaces function as collective sanctuaries. On the surface of it, femme centered Black salons might seem like a counterpoint to the male-dominated barbershop–a socially raunchy space where people reassess their hopes and dreams. It is not. The Black hair salon is one of the few intimate spaces demarcated for Black women, Black queers, and Black gender non-binary people. Our beauticians create a chamber to breathe better.

For the first 30 minutes, I sat in silence reading a novel. I was fascinated by Sara’s conversation with her younger sister. They began speaking French so I built up some courage and in French asked them where they were from.

“The Congo.”

“How long have you lived in South Africa?”

“Ten Years.”

“Why did you leave the Congo?”

No answer. They looked at me, stunned. Eventually explained that ten years ago a series of ever shattering events occurred in their home country. They had less access to food supplies, they saw their neighbors and kin targeted by a parable of violence, women were being raped. They were forced to flee and travel 4000 kilometers to this coastal city in South Africa. According to the Human Rights Watch, in 2010 nearly 3000 people were murdered in the Congo, 7,000 women and girls were sexually assaulted and 1 million people fled from the country. My ignorance was Eurocentric–I needed to do more work to understand African politics.

“Do you like living in South Africa?” I asked.

Sara lowly murmured, “I don’t want to answer a question that could be used against me.”

“Fair enough.”

Silence.

There’s no one way to braid Black women’s hair but there is care and diligence and difficulty when the hair is as short as mine. Using a fine comb, the hair has to be portioned in triangular or square patterns. Then the isolated fragment is combed, loosening the entanglements, the locks, the rough texture. Then with two strands of weave each step carefully interlaces the curly strands from one’s scalp until the weave and the hair form one unit.

Nigerians and Congolese migrants work in the same places, live in similar neighborhoods, attend similar churches and provide financial assistance to each other when in need.

With each braid, we began to exchange the stories of our lives as intimate strangers. We discussed the Congolese community in Durban and how they are becoming self-reliant within a sea of xenophobic attacks in South Africa. According to Sara and her sister, Nigerians and Congolese migrants work in the same places, live in similar neighborhoods, attend similar churches and provide financial assistance to each other when in need.

“We have to defend ourselves.”

This Black hair salon allowed us to speak to each other as progenies of different migrants—one within the African continent and one from outside the African continent. We bore the marks of Black people who survived French trans-Atlantic slavery and Belgian colonialism. Yet, our distinct pathways concerning travel and migration spoke to a new set of divisions that gestured towards class and cultural differences—strangeness and familiarity. There is a sense that we are all Black, with our tightly curled hair pressed against our head, high cheekbones, melanin-rich skin, echoing features from Nina Simone to Assata Shakur. Yet, it would not be fair to stick to these aspects alone. We spoke different languages, were accustomed to different foods and carried different passports. Other than the process of getting my hair braided, French and English the colonial links that gave us the space to communicate.

When I asked what they enjoyed about their job, they said that it gave them the chance to make others feel beautiful. Black hair braiders are an integral part of the central business district in Durban. Whether someone sets up a salon or has a small chair on the sidewalk, the people (mostly women and gay men) are accompanied by cassava dealers, electronic goods vendor, a panoply of spices, ripe fruit moldering in the sun, and bright cloth truncated for a tailor.

Black hair salons are microcosms of care that not only function as sites for hair grooming regimes but they become a space for care. Here, we trust our brethren to talk about our abortions, our badass children, and our infidel partners. Black hair stylists function as personal curators. On the surface, it seems like a simplistic client patron relationship, but it is more. This is a place that is part of a confluence for proverbial connections, an opportunity for cultural exchange, it is about knowing and unknowing.

2 in 1 Salon, Joe Slovo Park, Cape Town, South Africa – via Wikimedia commons

Nonetheless, hair care is therapeutic and it can be a place to alleviate the mental stress that Black people bear. Afiya Mbilishaka coined the term, “PsychoHairapy” referring to the way that traditional African spiritual systems provide culturally relevant relationships that promote healthy practices. This gives clients and patrons the space to bear one’s emotional troubles: the salon accommodates expositional stream of consciousness, with little judgment.

This encounter of being both familiar and strange, was one of the many tense moments during my first-time journey to sub-Saharan Africa

Near the end of my hair braiding session, my partner arrived, exciting the attention of the women. He was a white man that entered the space, challenging the racial categories that they had come to know. One woman offered him a ripe, nearly spoiled mango. He politely accepted, yet, later regretted this decision since the mango fibers would spend hours stuck between his teeth. When Sara was done with the last strand, she curled the ends of my hair, oiled my scalp, and took a picture for her records.

Very few people can contest the racial divisions in South Africa, yet, entering into the Black hair salon offered a new way for me to see and connect with other members of the African diaspora. This encounter of being both familiar and strange, was one of the many tense moments during my first-time journey to sub-Saharan Africa. My trip to this Black hair salon in central Durban was a multiethnic mélange of different strands of the African diaspora assembling in a nearly empty space where curly hair was conciliate in a semi-public intimate room. Hair braiders take stylistic risks with the instructions of their clients, deploying confidence where there had been none.